How I started to see my dad as a human

Happy Father's Day! I wanted to share my dad's story and how I learned to understand him just a little bit better.

Growing up, I never thought of my dad as a human whose upbringing, trauma, and hardships shaped the person he became. It's sort of the same way I felt about my teachers when I was a kid. Until I ran into my sixth-grade teacher at a weekend flea market, I subconsciously thought teachers lived at school and had no lives outside of grading papers.

With my dad, I saw him as more of a workhorse than a three-dimensional person. To me, “my dad” was associated with a very specific schedule. He was never home before 7 p.m., and when my parents ran multiple businesses, he left the house at 4 a.m. Basically, I never saw him before dinnertime.

Each night when we sat at the table, he wore a white tank top undershirt, which unapologetically showed off his deeply tanned neck and forearms but white-as-snow biceps. He wolfed down his food, chewing loudly and making clinking noises against the bowls with his chopsticks.

When he finished, he retired to the couch with the Korean newspaper shielding his face. It was the ritual that told us kids, this is dad time; leave me be.

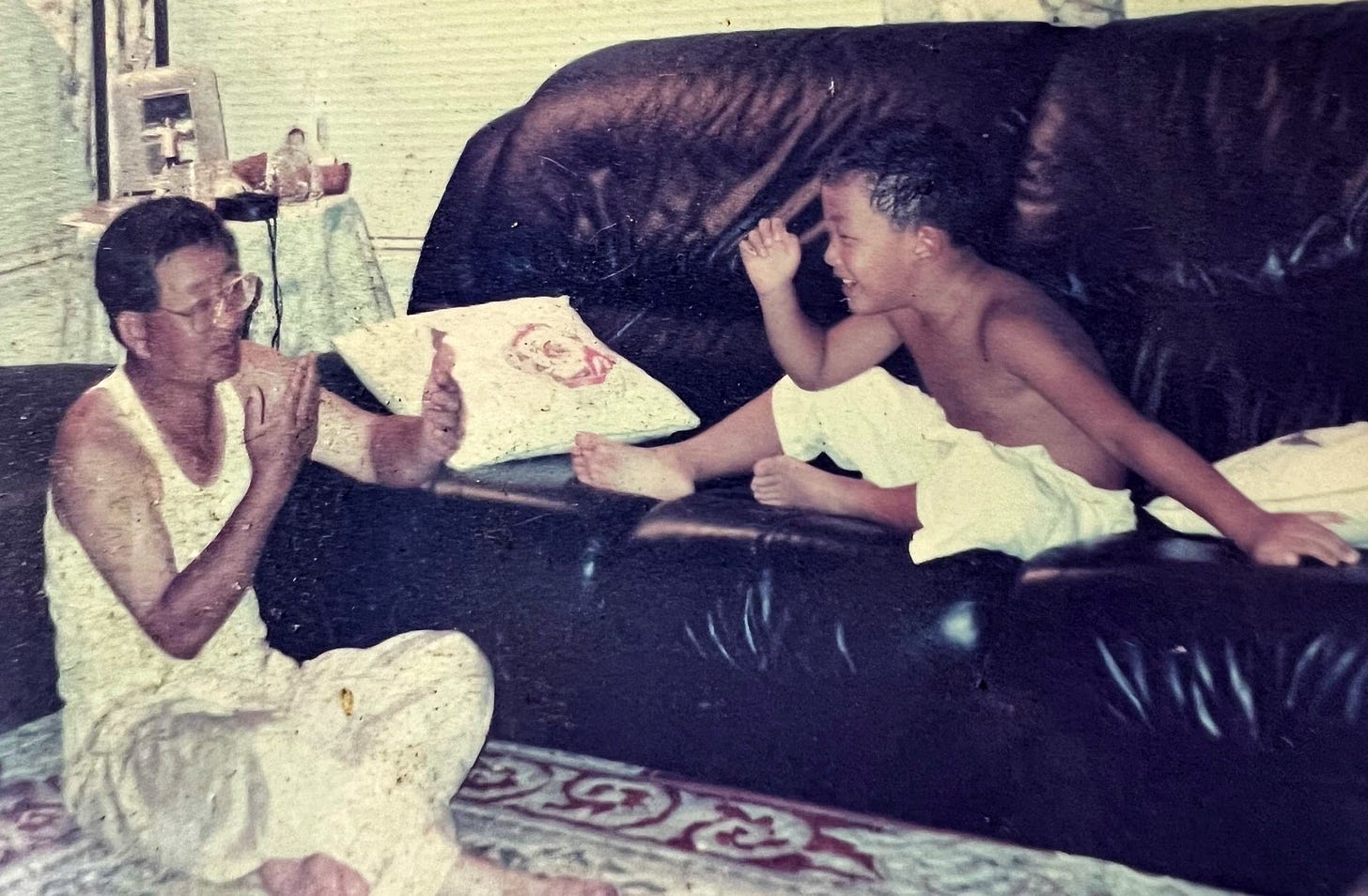

But he wasn’t always like that. When my brother was born, they played together. Before the age of 6, my brother was totally obsessed with my dad.

My dad wasn't a talker. Except for small talk mostly about school, he'd say stuff like, "Study hard. Work hard." It was his simple way of parenting, I guess.

I never really knew what else to say to my dad either. I filled out entire white spaces in Hallmark birthday cards to my mom, while ones to my dad would be signed with my name and a generic one-liner, "Thank you for always working hard."

When he wasn't manning the store, he was off playing 18 holes. When I was 16, I watched the store for him on Sundays so he could have one measly afternoon to himself.

He worked like a dog seven days a week, so any moment of freedom he got, he was on the green, working on his putts and whatever else golfers do to improve their game. In the evening, he returned two shades darker, his hair smashed up and sweaty from wearing a cap all day. Sometimes he smelled like Korean BBQ and his breath was stale from Coors light. It told me that he got to partake in some post-golfing food and drink with his buddies at a Korean restaurant.

The only time he didn't work was in 1992. It wasn’t by choice though, it was because our store burned in the LA Riots.

For nearly a year, neither of my parents had to rush off to work. I was a sophomore in high school and I remember how odd it felt to see my dad when the sun was still out—like he was some vampire father I only saw at night.

It was also the only time we traveled as a family, taking bus tours to San Francisco and Yellowstone with other Korean families.

A physical decline

I feel ignorant, but I admit I only recently started seeing him as a person when his health began to decline a few years ago. Perhaps it's because I realized he wasn't invincible or some robot who just worked all the time.

Maybe it was his thinning hairline, shrinking frame, and the slight heartache of watching someone get old. I can't be sure exactly what caused me to start changing the way I felt about him.

My dad was diagnosed with diabetes in his 50s. In his late 70s, he began to experience neuropathy caused by his diabetes. It's mostly in his legs, but he also feels numbness in his hands, which are always cold. His thick fingers, which once bounced quickly off of the cash register at the store, are no longer precise. These days, he can’t even button his shirts. He's in constant pain.

In two short years, he morphed into a thin grandpa. I felt like it happened overnight, even though I recall wincing inside each time I came home to visit because he looked so frail.

Illness is cruel—taking away my dad’s ability to drive, swing a golf club, or go on a brisk morning walk to the park. His life was suddenly subjected to the soft easy chair my sister had bought for him.

One day you're consumed with running a store; the next, you're hobbling like a toddler from the recliner to the bathroom. I felt terrible.

Seeing stories everywhere

In writing my book, I began seeing the world through a different lens—one that illuminated stories all around me.

I wanted to know more about my parents. They told me little stories here and there, but nothing too in-depth.

I knew enough to understand my dad’s upbringing was complicated and sad. He was an orphan by the time he was in his early teens. He didn’t really know his dad and his mom died suddenly.

Both my parents grew up poor. But unlike my dad, my mom had three younger siblings and a tight-knit family with two parents that loved all of them deeply.

Now that I'm an adult, I see how these differences affected the way they parented my siblings and me. While I was growing up, my mom was affectionate, smiley, and warm. My dad was… well… hidden behind the Korean newspaper.

A few months back, I captured the first recording with my parents. We talked about what they went through during the LA Riots. Lucky for me, my dad has a memory like an elephant and at nearly 83, he’s incredibly sharp. Eventually, I'd love to turn these recordings into a podcast series.

The time my dad was a 'slave'

One day while visiting my parents not long ago, my dad announced, "I was once a slave."

Record scratch—errk… huh?

I know he was trying to shock me, and I totally fell for it.

"When were you a slave?" (I wondered how politically incorrect it was for him to say he was a slave, but then again, my dad still calls Asians "Orientals." I think I tried to correct him by saying, servant.)

"Yeaaaaah, I was," he insisted. "When I was five."

My dad was born in 1940 and when he was a wee boy, Korea was colonized by Japan. There was no North or South Korea—it was one nation. My dad lived north of Seoul and close to Pyeongyang (today’s capital of North Korea).

At a time when he should've been learning about colors and shapes and phonics with other little kids, he was working as a child servant to a wealthy-ish family. He told me that when you were poor—and most people in Korea were dirt-ass poor, you worked, even if you were a child.

Each day, my dad went to the house of this well-off family, gathering firewood in the forest, cleaning, and running other small errands. I am still learning how the Japanese occupation affected his ability to attend school then. (A question for a future recording.)

Wide-eyed, I asked my dad, "How much did you get paid as a servant?"

My dad scoffed. "Paid? I got a bowl of rice."

And that's when it hit me—who cares about money when you’re hungry all the time?

One day, he was in the forest gathering wood when a high school kid spotted him. He approached my dad and asked, "What are you doing? Where's your mom?"

My dad replied that he was working for the family down the way and that his mom was at home. The high schooler insisted my dad take him to his mother.

When they arrived at my dad's house, the high schooler informed my dad's mother that the Japanese had mostly left Korea and that times were quickly changing. "Little kids like your son are going to school now. He needs to go to school."

My dad's mother, who I understand to be a forward-thinking woman for the times, listened to what this kid had to say. Shortly after, she put my dad in school.

Just like that, his days as a servant boy were over. But it was hardly a happy ending.

My father's father, a war, and death

In 1950, the Korean War broke out. By then, my dad was 10. My dad, his mother, and brother immediately fled to the South. At the time, my dad’s father was at work. There were no phones or any other way to reconnect them again. He never saw his father again.

Also, this is kind of an important part of the story—my dad’s father already had two other families and my dad’s mother was the third wife. Polygamy was normal in those days, but it was a big reason why my dad never really knew his father.

There's a hierarchy between families, so if you're not the first family, you're last in line for money. With multiple wives and families, the living situation is dependent on the husband’s income. A decent wage meant the families likely lived in separate houses.

My dad lived in a different house, but his mother still had to fend for herself. She ran a ha-sook with her friend. Back then, a ha-sook was like a poor man’s version of Airbnb. The renters were primarily bachelors who slept in the same room (probably packed like sardines) and got home-cooked meals when they returned from work.

I don't know how much love my dad received from his mother before she died. My dad was maybe 13 or 14 and probably felt the shock from her early death—she succumbed to injuries from bomb shrapnel. From that point on, my dad was on his own, working during the day and going to school at night.

As for his father, it would be another 40+ years before my dad learned what happened to him. He discovered that his father lived in the next town after the war broke out and they escaped to the South. Like his mother, his father died young—he was in his mid-forties. When I asked my dad about his father, the response he gave made me feel like he didn't get the warm fuzzies. I got the feeling that, as a child, he felt unimportant.

When I think about this story and what my dad went through, it feels unreal, like it's a story from an alternate universe or a movie. I am reminded of Apple TV's hit series, "Pachinko." That may be why my dad binge-watched it in two days.

I used to wonder why my dad wasn't more involved as a dad. Why he never wanted to talk to me or know more about my life. Now I know it's because he didn't grow up with parents. He grew up in survival mode.

As a dad, I think he believed he was doing his best by working all the time and providing. It was his quiet way of being a great dad.

I'll never fully understand it, but growing up without parents affected his ability to be the kind of dad who openly communicates with his kids and wants to be involved in their lives.

Good or bad—it's a part of who he is. It's the part of him that is so incredibly disciplined and, when he was working, so stubborn and intimidating.

I think he uses it as his superpower. He’s exercising and walking again rather than sitting around all day on his recliner. He still walks with his walker, but he’s motivated and is out of the house more often.

Happy Father's Day, Dad. You inspire me to do my best every day.

The other day my mom sent me this video of my dad. Just a few months ago, he could barely make it from the bathroom to the living room. In the video, my mom says, “You’re walking faster than me.”

More stories…

Memoir flashback: The time my dad got shot

In chipping away at my memoir, I’m reliving parts of my life that doesn’t exactly make me feel warm and fuzzy. From my soul-crushing days of working in Silicon Valley to my divorce to conjuring up weird childhood stuff, it’s both a reminder of what I’ve been through and how much I have to be grateful for. Writing it all d…

Memoir Flashback: Remembering my mom's love when I was a latchkey kid

As far back as I can remember, my mom was a working mom. When I was three, she put me in my yellow stroller and took me to work where she was a sewer at a factory. I remember the dark and dreary downtown L.A. factory with…

Wow. This was captivating. It’s so hard to think about our parents as human sometimes. I’m just beginning to scratch the surface with mine. Thanks for sharing this. 🩵

Engaging story. I was in LA during the riots. So sorry about your parents’ business. Were they able to rebuild?